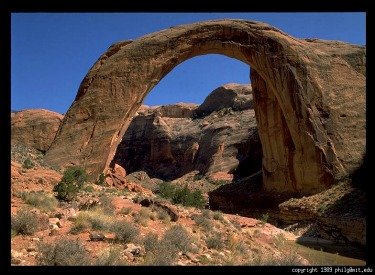

Rainbow Bridge...

One Of The Seven Natural Wonders Of The World?

National Park Service Photo

Rainbow Bridge is truly a wonder, a marvel of nature.

But does it qualify to be among the top seven natural wonders of the world?

Some would argue that it does. But, if you compare it with the Grand Canyon, Bridal Veil Falls, Niagara Falls, Angel Falls, the Great Barrier Reef, the Sahara Desert or Mount Everest, I believe it falls short.

But whether it does or does not compare to these great natural wonders, it is certainly beautiful and magnificent and in a class of its own.

Like all of these natural wonders, it is an ancient tribute to the forces of nature.

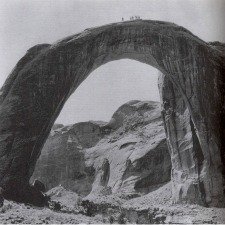

Rainbow Bridge is said to be the largest known natural bridge in the world at 290 feet tall and with a span of 275 feet.

At the top it is 42 feet thick and 33 feet wide. It is almost as tall as the Statue of Liberty.

Each year, more than 300,000 people visit this National Monument, and I am sure many of them would not agree with my assessment that it does not belong among the Seven Natural Wonders of the World.

But, regardless of how it is viewed, Rainbow Bridge is a must see.

And the best way to see it is by boat.

Don’t worry if you didn’t bring your own boat, because you can easily rent one or take one of the Lake Powell tour boats.

Just be sure to make advance reservations. ( See below for tour and rental companies and their telephone numbers).

|

|

|

|

Men On Top Of Rainbow Bridge |

Aerial View Of Rainbow Bridge |

National Park Service Photos

Rainbow Bridge or Nonnezoshe ( “rainbow turned to stone,”) as it is called by the Navajo, was in all likelihood first discovered by the Anasazi, the ancient people known to have populated this area several hundred years ago.

The Navajo and Paiute Indians, who followed in their footsteps, considered it a sacred place, and, in fact, petitioned the US Government to close it to visitors.

In a concession to this petition, in 1995, The National Park Service erected a two foot high rock wall along the trail approaching the bridge and revised the Park brochure stating:

“Approach and visit Rainbow Bridge as you would a church.”

And, on the wall is a sign advising visitors:

|

“American Indians consider Rainbow Bridge a sacred religious site. Please respect their long-standing beliefs. Please do not approach or walk under Rainbow Bridge.” Have A Great Story To Share?Do you have a great story about this destination? Share it! |

Books about Rainbow Bridge may be purchased through Amazon.com by clicking the link below.

|

The bridge was not “officially” discovered (i.e. by the white man) until August 14, 1909, and on May 30th of the following year President William H. Taft made it, and the 160 acres surrounding it, a National Monument.

Please see below for a condensed history of this “discovery.”

As a side note, the area surrounding Rainbow Bridge National Monument was established in 1972 as Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

Thus, Rainbow Bridge is a National Monument within a National Recreation Area.

|

|

|

|

Rainbow Bridge Boat Dock |

Rainbow Bridge Floating Dock |

National Park Service Photos

Page, AZ Current Weather and Forecast

This monumental stone bridge cannot be accessed by road.

The only way it can be reached is by boat or a several hour hike from either of two trailheads in the vicinity of Navajo Mountain.

Both of these trails should be considered only by experienced hikers.

Permits are required and may be obtained from the Navajo Nation. (See the link below).

It is approximately a two hour boat ride from Wahweap or Antelope Point Marina near Page, Arizona.

At the end of the boat ride there is still a mile-long walk from the National Park wharf in Bridge Canyon before you reach the bridge.

But, don’t despair. If you don’t feel you can handle the walk, you will still be able to see the bridge from the wharf.

There is not a visitor’s center at the bridge nor are there restrooms or drinking fountains, so you should come prepared.

|

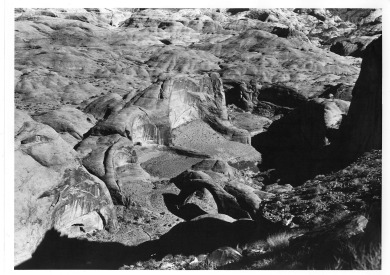

The Geology: Much of what I refer to as Lake Powell Country is located within the Colorado Plateau, an area of 130,000 square miles roughly straddling the four corners area of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Colorado. Over millions of years, perhaps as many as 500 million, sediment from rising and vanishing seas was deposited across this vast area, eventually solidifying into layers of sandstone. |

Mother Nature then used this sandstone as her canvas. Where there were rock walls, she created windows and arches like those we find at Arches National Park.

Where there were rivers and streams, she sketched canyons and bridges. And, so it was with Rainbow Bridge.

Over

these countless years, water flowed through Bridge Canyon, sometimes

rushing and flooding, sometimes just a lazy, meandering flow, but always

cutting and scouring.

Following a course of least resistance, it cut through the softer sandstone and flowed around the harder more resistant stone.

Where the water created wider bends, eddies formed, and the swirling water cut into the soft sandstone, wearing it away, creating fins extending from the canyon wall.

Through sheer persistence and relentless pounding against these fins, it finally cut through the stone, creating a hole and, like a hole in a dike, grew larger as the river flowed through it.

And a few short million years later, as the river cut deeper and wider, we have Rainbow Bridge. A bridge sculpted from the top down.

View From Cummings Mesa

National Park Service Photo

The History:

Like Lake Powell, Rainbow Bridge has a controversial past.

A controversy over which white man was the first to set eyes upon it on August 14, 1909.

The story begins with John and Louisa Wetherill who owned and operated a trading post at Oljeto, Utah on the Navajo Reservation.

John Wetherill was deeply interested in archaeology, and had a passion for Indian artifacts.

To supplement his income from the trading post, he hired himself out as a guide and outfitter to others who were likewise interested in archaeology.

Two such people were Byron Cummings, amateur archaeologist and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Utah, and William B. Douglass, a bureaucrat and surveyor for the General Land Office in Washington, D.C.

He was a strong proponent of the 1906 Antiquities Act which was enacted by Congress for the preservation of American Antiquities.

I won’t go into the long story of how each man learned of this hidden bridge, and what motivated each of them to find the bridge.

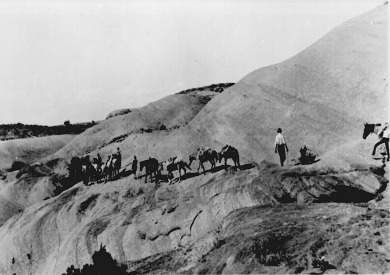

Let it suffice to say, that late in the day on August 10, 1909 Byron Cummings, Neil Judd, Cummings’ nephew , William Douglass, John Wetherill, and a Paiute Indian guide named Mike’s Boy who was supposed to know the location of the bridge, and seven others, set out to find the “Rock Rainbow that spans the Canyon.”

On August 12th, they stopped at the farm of Nasja Begay, who was a Paiute Indian guide often used by John Wetherill.

However, Nasja Begay was not there. His father said he had gone to check on his family’s sheep, but he would get word to him to meet the party north of Navajo Mountain.

Men and Horses on Slickrock

National Park Service Photo

The group continued on, but it soon became evident that the guide, Mike’s Boy, was unsure of the route.

The country was rugged and dangerous and they expended a lot of time and energy backtracking and looking for ways in and out of canyons and across creeks and rivers.

On the evening of the fourth day, the exhausted group of men and animals pitched camp in what is now called Surprise Valley.

Understandably, their spirits were low. But, then around 10:00 P.M., from out of the darkness surrounding them, Nasja Begay entered the camp.

This was almost of miraculous proportions; that he could even find them in this wild and vast country was in itself incredulous, but that he found them in the dark bordered on the supernatural.

But find them he had, and he said he knew the way to the stone rainbow, that it was near and that he would lead them to it the following day.

This news must surely have caused a renewal of energy and enthusiasm, and the group set out the following morning with high spirits.

|

With their quest so near and anticipation so high, there became a jockeying for position between Dean Cummings and William Douglass, each man wanting to lay claim to being the first white man to see the magnificent stone bridge. In his report to the General Land Office, William Douglass wrote: |

“For three hours we rode an uncertain race, taking risks of horsemanship neither would ordinarily think of taking, the lead varying as one or the other secured the advantage over the tortuous and difficult trail.”

Rainbow Bridge

Photo Courtesy Philip Greenspun

William Douglass was in the lead when the party rounded the final bend that revealed the bridge.

Wetherill, Cummings and Neil Judd, Cummings’ nephew, rounded the bend somewhat behind Douglass and when they saw the bridge they stopped to admire the sight.

Douglass continued on, and they shouted at him to come back to where they had stopped.

Douglass, who was hard of hearing, did not stop and hurried toward the Bridge.

But, Wetherill, not to be outdone, raced to the bridge, passed Douglass and was standing under the bridge when Douglass and the other members of the group arrived.

It is not clear whether Douglass saw the bridge when he rounded the same bend where the others had stopped, but Byron Cummings claimed first sighting for himself.

Douglass would later write :

“They planned to beat me to it, but failed, as I reached it before Cummings.

I made no effort to get in front of Wetherill any more than I did to get in front of the Indians.”

And so it went for the next 40 years with no agreement reached among these men as to who actually saw the bridge first and who was the first to reach it.

I think they would all agree, however, with Neil Judd’s assertion, when he wrote in the National Parks Bulletin in 1927:

“Who actually discovered Nonnezoshe?

Nobody knows.

Some Indian way back in that pre-Columbian past when man romped and roamed widely over this continent of ours but left no written record to prove it.

Some Indian was the real discoverer.

But we whites have a conceit all our own which frequently tempts us to ignore the achievements of those of a different hue.

A thing clothed in the traditions of a thousand years remains unknown until we ourselves have seen and recorded {it}.”

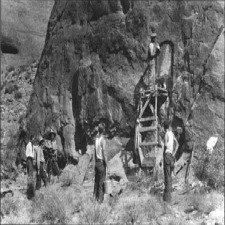

Commemorative Plaque Being Placed

National Park Service Photo

In 1927, the National Park Service erected a bronze plaque at Rainbow Bridge honoring Nasja Begay.

The plaque read:

“To Commemorate the Piute {sic} Nasja Begay Who First Guided The White Man To Nonnezoshe August 1909.”

It was not until the early 1980’s that Mike”s Boy, who was now known as Jim Mike, received recognition for his part in the expedition which “discovered” Rainbow Bridge.

The NPS mounted a smaller bronze plaque beneath that of Nasja Begay.

If you are interested in reading a more complete history of Rainbow Bridge, I suggest you follow the links below:

http://www.nps.gov/rabr/historyculture/upload/RABR_adhi.pdf

http://www.nps.gov/rabr/historyculture/upload/Stephen%20Jett%20Article.pdf

Boat Rental and Boat Tours:

ARAMARK:

• Wahweap… (928) 645-2433

• Toll Free…(800) 528-6154

Antelope Point:

• (928) 645-5900

Navajo Tribal Permits

http://www.navajonationparks.org/permits.htm

References:

THE GREAT “RACE” TO “DISCOVER” RAINBOW NATURAL BRIDGE IN 1909

STEPHEN C. JETT

Department of Geography

University of California, Davis

Davis, CA 95616

A BRIDGE BETWEEN CULTURES:An Administrative History of Rainbow Bridge National Monument

By David Kent Sproul