Navajo

Bridge…

Spanning the Grand Canyon

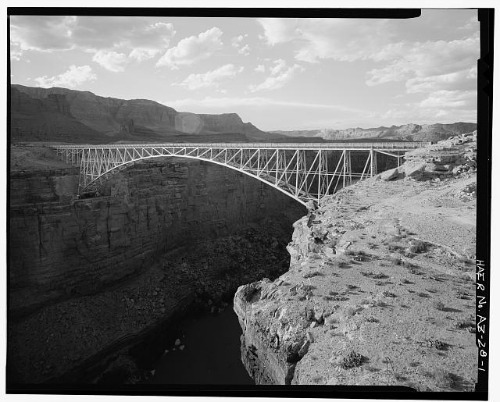

Rising 464 feet above the Colorado River, Navajo Bridge was opened to traffic on January 12, 1929.

At the time, it was the first steel deck arch built in Arizona and the highest highway bridge in the world.

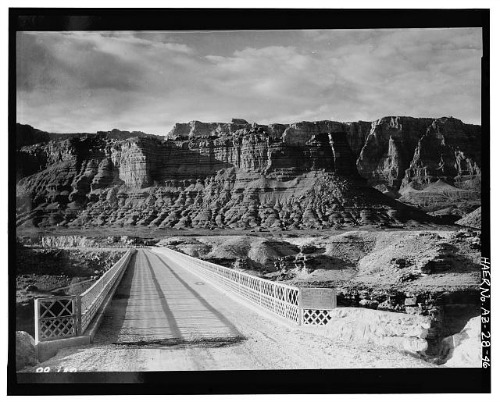

Navajo Bridge Overview - Facing North

Photo: Courtesy Library of Congress

More importantly, it bridged the states of Arizona and Utah and the sprawling Navajo Indian Reservation.

And, of only slightly less importance, it opened up the north rim of the Grand Canyon National Park to both Arizona and Utah.

The Bridge at a Glance:

|

Location - Marble Canyon - 13.8 Miles N Jct US 89 |

Builder/Contractor – Kansas City Structural Steel Co. KC, MO The bridge was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 13, 1981 |

Justification for Navajo Bridge:

“Of all the obstacles to overland transportation in the West, none was more formidable than the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River.

Explorers, pioneers, teamsters, engineers and others have sought a way to cross the yawning gorge ever since its tentative explorations by Spanish missionaries in the mid-18th century….

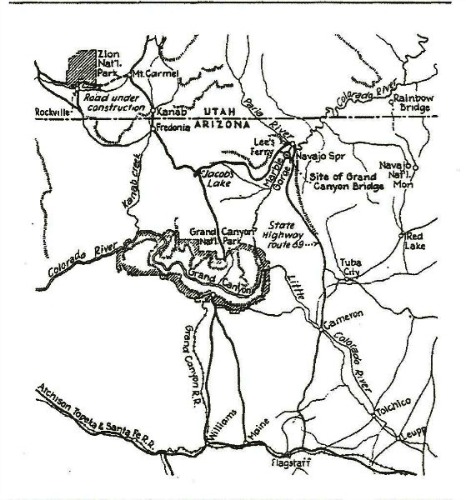

Navajo Bridge Area Map

Travelers attempting to reach Utah … followed a county road north from Flagstaff through the sprawling Navajo Indian Reservation.

This route crossed the Little Colorado River at Cameron, over a suspension bridge that had been erected in 1911 by the Office of Indian Affairs.

From Cameron the road extended 25 miles north to Tuba City.

There it branched into two routes - one northeast to Kayenta and southeastern Utah, the other northwest to Lee's Ferry and then to Kanab, Utah.” 1

This road was little more than a desert trail and generally only passable in good weather.

Even with good roads, Lee’s Ferry would still be the “fly in the ointment.”

“The descent from the rim to the canyon floor was winding and precarious, the process of loading and unloading the ferryboat slow and cumbersome, and the crossing over one of the most unpredictable rivers in the West was often dangerous or impossible.

For wagon traffic these difficulties represented a major inconvenience; for automobile traffic they were intolerable.

By the 1920s it had become clear to officials in Arizona and Utah that a permanent bridge high above the canyon floor was needed to facilitate commerce in the region.” 2

Planning Stage:

In 1923 the Arizona Highway Department (AHD) began making plans for a bridge over the Colorado River at Marble Canyon near Lee's Ferry.

This was the narrowest place between canyon walls, 585 feet, of any place along the river in Arizona.

Since the east end of the bridge would be on Navajo Nation land and they would profit economically from the traffic generated from the bridge, the US Indian Service petitioned Congress for $100,000.

In December 1923 Congress allotted $100,000 of Navajo tribal funds for the Grand Canyon Bridge and with funding from the State of Arizona of $290,000, “…AHD contracted with the Kansas City Structural Steel Company (KCSSC) in June 1927 to fabricate and erect the [steel deck] arch.” 3

Side Bar:

KCSSC’s contract was for fabricating, transporting and erecting the bridge only.

It did not include the foundation work, the approach work on either side of the bridge nor any other work not associated with the fabrication and erection of the bridge.

AHD, along with Coconino County and the Tuba City Indian Agency had agreed to do this work themselves.

Logistics:

“The first major hurdle to be overcome – indeed, the single greatest hurdle of the project – was the transportation of some 3.2 million pounds of materials, supplies and equipment over the 130 miles from the railhead at Flagstaff to the bridge site.

With little improvement since the 1910s, the road north of Flagstaff was still no more than a trail in many places.

And with temperatures ranging from 110° to 16° below zero, the travel conditions varied wildly.” 4

KCSS contracted with E.M. Moores & Sons of Clarksdale, Arizona to deliver the material from Flagstaff to the bridge site upon the condition he deliver 10 tons per day.

In order to accomplish this, Moores & Sons used two trucks, a 5-ton and a 12-ton.

Limited by the size of the trucks and the capacity of the Cameron Bridge, rated at only ten tons, the largest steel members were 53 feet long and weighed 12 tons.

In order to accommodate the larger loads, the Cameron Bridge had to be strengthened before it could be used.

Since it was on Tribal Land, the United States Indian Services (USIS) agreed to do the work.

Meanwhile, in the Kansas City plant of KCSS, the components for the bridge were being fabricated from steel rolled by the Illinois Steel Company.

The first erection equipment left the plant on January 5, 1928; the first structural steel two weeks later.

In all, some fifty carloads of material was shipped by train to Flagstaff, where it was loaded onto Moores & Sons’ two trucks.

“Moores’s drivers negotiated steep grades, sandy washes and deeply rutted roadways, taking between 13 and 20 hours for the 130-mile trip. They were able to trade off with other drivers from a road camp set up about halfway along the route….” 5

A camp was set up on the south side of the river to store the material until it was needed.

Much of it could be transported to the other side by an overhead cable which had been erected for that purpose.

However, vehicles and some supplies had to be transported across by using the old ferry; this proved to be a very dangerous undertaking.

On June 7, 1928, 3 people died when the ferry capsized while attempting to cross the river.

The ferry was replaced with a 16 foot rowboat powered by an outboard motor which continued to carry material across the river.

“This did not lessen but increased the danger of crossing the river,” AHD engineer W.R. Hutchins said. “I have seen the boat loaded until it was invisible.” 6

Construction:

Meanwhile, AHD crews were busy with the arduous and dangerous work of “…digging or blasting some 9,000 cubic yards of material in order to place the arch foundations on solid footing.”

By November of 1927, the excavations were complete and work on the concrete footings had begun.

By the following April the foundation work on both sides was complete and ready for KCSS to begin work on the anchorage of the south arch half.

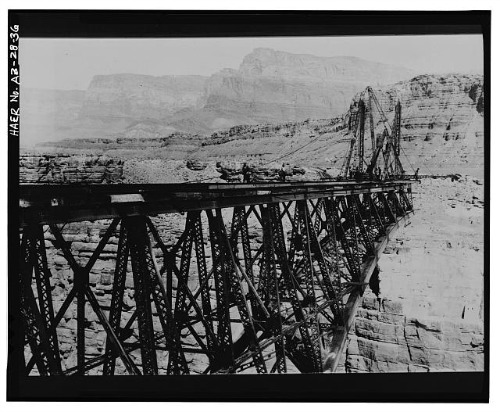

South Arm Of Navajo Bridge

Photo: Courtesy Library of Congress

By June 14, 1928 the first half of the arch was in place and they began work on the north side.

Side Bar:

The same week that the eleventh panel on the Flagstaff side was riveted in place, June 15, 1928, LaFayette McDonald of Kansas City, Missouri, slipped from a beam and fell to his death.

His body was never recovered from the river.

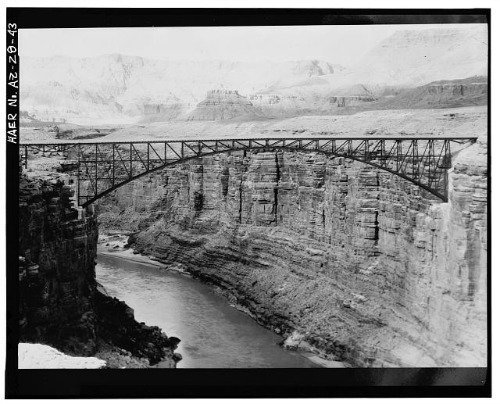

In just a short two months, the steelworkers had the second half in place, and on September 12, 1928, the crew was ready to lower the two arch halves and couple the center pins.

Navajo Bridge Completed Spans

Photo: Courtesy Library of Congress

They started early the morning of the 12th and by 9 Pm the halves had been joined and the span was complete.

Although the most hazardous work was done, there was still much work left to do such as pouring the concrete deck and grading the approaches.

Navajo Bridge Entryway

Photo: Courtesy Library of Congress

Finally, on January 12, 1929 the last of the work was completed and the Grand Canyon Bridge was opened to traffic “…with only a few laborers and engineers present while a cold wind blew through the canyon.”

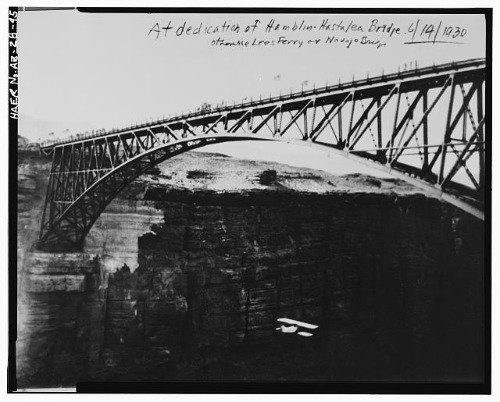

Navajo Bridge Dedication Ceremony

Photo: Courtesy Library of Congress

Dedication:

Grand Canyon Bridge was officially dedicated on June 14 and 15, 1929, as reported by the Arizona Republican:

“Under a typical Arizona cloudless sky, the heat tempered by a gentle south breeze, the Grand Canyon Bridge across the chasm of the mighty Colorado river (sic) was formally dedicated by four governors of neighboring states this afternoon in the presence of a crowd of more than 5.000 persons, representatives of at least 20 states. As movie and other cameras clicked and with three other chief executives of as many states standing by. [Arizona] Governor John C. Phillips clipped the purple and yellow ribbons which represented the breaking of an age-old barrier between the lands to the north and south of the Colorado river (sic). Miss Elizabeth Phillips, daughter of the governor, christened the bridge by breaking a bottle of Colorado river (sic) water over the railing. Governor Phillips, who was standing at her elbow, was well sprinkled by the water, as were dozens standing near." 7

Bi-Plane Flying Under Navajo Bridge During Dedication Ceremonies

Photo: Courtesy Library of Congress

Significance:

• It was the first steel deck arch built in Arizona and the highest highway bridge in the world.

• It was the only crossing of the Colorado River in some 600 miles.

• It provided a valuable tourist route to Grand Canyon National Park and the rest of the state.

Have A Great Story To Share?

Do you have a great story about this destination? Share it!

References and Resources:

1 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD

National Park Service

Department of the Interior

P.O. Box 37127

Washington, D.C. 20013-7127

Clayton B. Fraser

Fraser design

Loveland, Colorado

September 1993

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/az/az0200/az0251/data/az0251data.pdf

2 - 6 Ibid

7 "Grand Canyon Bridge Dedicated in Ceremony Led by Governors,"

[Phoenix] Arizona Republican, 14 June 1929.